Magic à la Cigale

Benedetta Castrioto

This is a magic spell, a prayer, a mantra, an exorcism. Why? What do I need? Maybe a blessing. A ritual for auspicious pauses. So they can be meaningful again, and free us from the splitting pulls of productivity and distraction. So I can invite others with me in these pauses, to dissect the world and build meaning together.

I started thinking about pause a few months ago. It followed a year of work and a lifetime of interest in the question of labor. How we labor, what for and why. What forms of labor are recognized by our society and how they are valued. And then I began to wonder, what the time we have outside of employment is for and how we make it worthwhile. Might idle time be generative? These are some of the preoccupations that led me to this research and eventually to Montegiovi.

A temple for pause

It all began with a boring hour: a time to do nothing and just be, without chores, entertainment, or distractions. I first made up the practice after seeing a couple, in Accra, standing outside their home in the evening, chatting and nothing else. How long had it been since I had been in the company of others like that, effortlessly present, without a mediating screen, the excuse of a meal or something else…

In Montegiovi, I saw a similar, spontaneous ritual: neighbors meeting up in the evening, on benches, to chat while enjoying together the heat of the day dying out. A simple convivial moment, that needs no invitation or pretext, sufficient in and of itself. During my days there, a few people repainted all the benches of the town afresh. A sign, to me, of the importance of these mundane meeting and rest places, which are cared for by the collectivity. To paint them for the community, I thought, is meaningful labor. And those benches began to seem like a temple for pause.

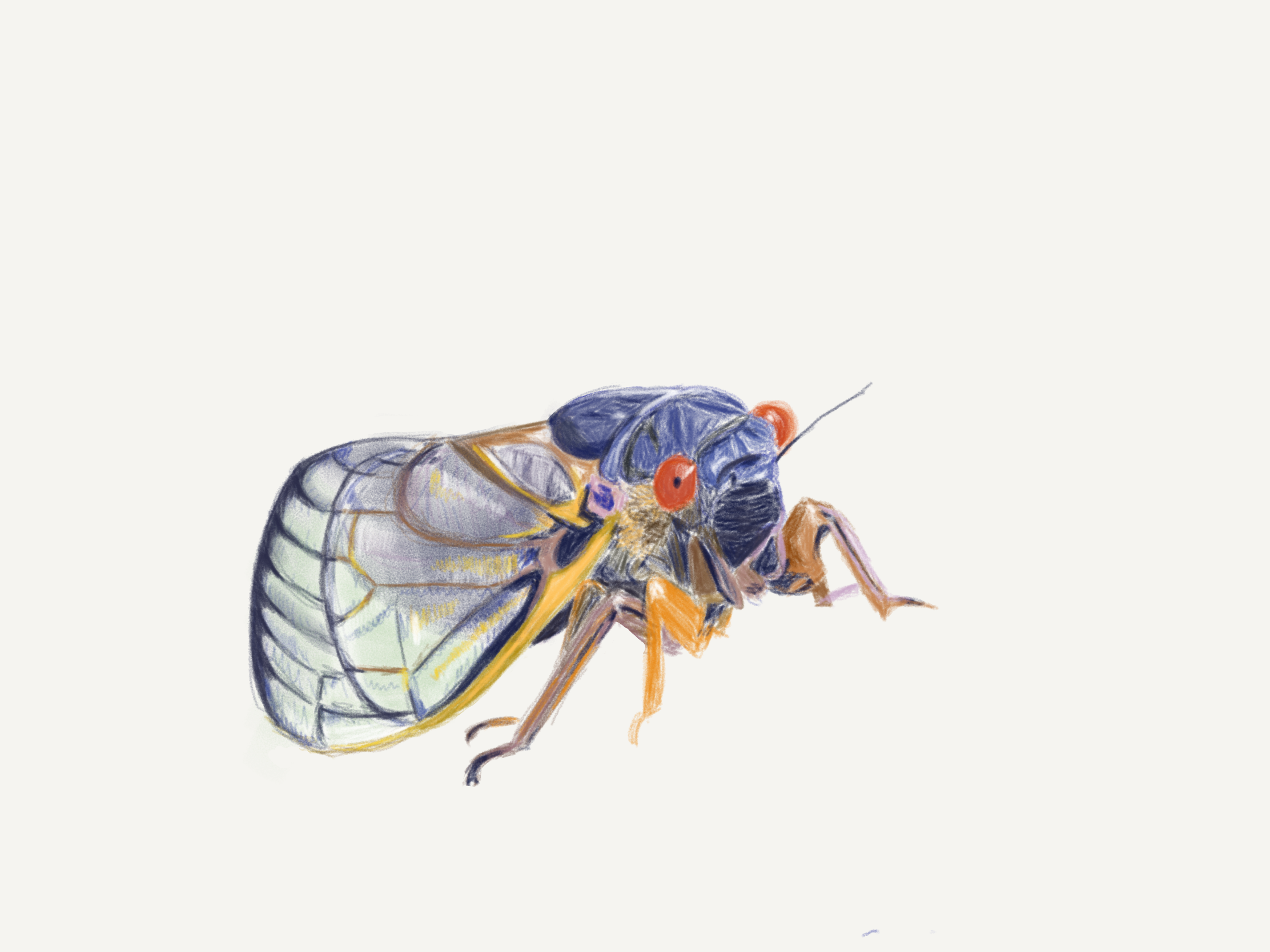

I visited the temple myself, meeting in the evenings with another La Baldi resident, Olimpia. There’s an affinity between us. We exchanged thoughts and smoked her cigarettes. We talked about womanhood and motherhood, about the periodic cicadas of America, called, fittingly, magicicadas, about art and magic, the bella ‘Mbriana — Naples’s guardian spirit of the home —, sickness and death, and about sempervivum, a humble plant, that never dies[1], which Charlemagne wanted planted on top of every roof of the Sacred Roman Empire, and which was said to protect homes from lightning. We talked in the temple of pause, and the cicadas sang.

Prophets of pause

Sometimes a symbol is a shortcut to an idea, sometimes it is a scenic route to it. Cicadas are traditionally symbols of summer, of slow hours in the heat. Music of the quiet, Byron’s ‘people of the pine’, but also of the oak, the olive, and the linden tree. Sitting in silence in the garden, every day, I could hear two distinct choruses. One a continuous hum, the other an intermittent and fast pulse. They measured my time, like music would, and made it seem eternal. A few times a deep roar in the air above interrupted for a long moment: military planes practicing. Meanwhile ants walked and foraged quietly. Scientists estimate there may be 2.5 million of them for every human on earth (maybe more), so if ants weren’t quiet perhaps, we wouldn’t hear much else.

The cicada and the ant are a proverbial couple[2]. I remember from childhood Aesop’s tale. It seemed to make sense then and now it leaves me perplexed. The cicada sang all summer long, the story goes, while the ant worked to save supplies for the winter. When winter came, the cicada had nothing to survive on and asked the ant for help. The ant mockingly denied it and the cicada died. A story, supposedly, about the value and importance of hard work...

Not much is known with certainty about Aesop. He is believed to have arrived in Greece in the 6th century BC as a slave, been sold to a philosopher and later freed for his help to the people of the Island of Samos.

Another Greek story on cicadas’ single-mindedness, comes, 200 years later, from someone who probably owned slaves, Plato[3]. In Phaedrus, he has Socrates tell us that cicadas were once humans, who loved making music so much that they forgot to eat and died. The Muses rewarded this complete dedication to art by transforming them into cicadas, beings that sing all day and can live on almost nothing[4]. Since then, when cicadas die, they report back to the Muses on the humans most committed to honoring them.

In both stories the misunderstood creatures unwittingly find themselves in a controversy over the virtues of laboring for passion versus laboring for sustenance[5]. If in the first one dying of hunger is presented as the animal’s fitting natural punishment, in the second it is an achievement and a merit that calls for a divine blessing.

Both stories seem misguided though, implying that cicadas sing for some ideal form of passion that has nothing to do with living, that passion isn’t about survival. Aesop disregards the sacrifice and labor of singing ceaselessly. Socrates ignores the cicada’s biological imperative to sing (the rather sexual nature of that passion), and Phaedrus, his dialectic partner, mistakenly sets mental pleasures and labor apart from physical ones.

As it turns out, nature seems to offer the best lesson about cicadas and ants: the average life of a worker ant is 1 to 3 months, so summer harvesters will never live to see winter (a colony’s queen can live years though — 28 years is the longest lifespan ever recorded). Annual cicadas, on the other hand, live for 2 to 5 years. Magicicadas, the periodic kind, 13 to 17 years. Both spend most of their life in silence, under ground as nymphs, until they surface for the last few weeks of their life to mate, for which the singing is essential. Singing, like foraging, is an instinct. Foraging, like singing, is culture. Both are labor.

Cicadic enchantment

I was in Montegiovi on the night of St. John’s, the most magical night of the year, they say. A syncretic belief that blends pagan rituals of the summer solstice and the Catholic celebration of the saint. I learned that St. John’s day is traditionally when walnuts are harvested. And on this night, you can make magical water, soaking flowers in it and leaving it out from sunset to dawn. I learned these things on my brief trip to Umbria. I went to the Morica springs and swam in freezing water and marveled at its incredible blue color and its transparency. So clear that I could see nine meters deep, from the tips of the river algae reaching the surface, all the way down to their roots. At the gardens nearby they were preparing St. John’s water. I didn’t have time to stop and make some. I thought maybe I could do it later at home, with the lavender from the garden. But I didn’t. It did not make sense to do it alone. Magic is meant to be shared, perhaps because we are all skeptics deep down, and we find the confidence to believe only when others do it with us. That’s kind of the point of organized religion, I suppose.

I told Olimpia and she recounted a ritual from her childhood, called, in some parts of Italy, i puositi. A group of women would gather at home. They would prepare 24 small wooden sticks and roll each one up in a piece of paper. Holding one of the sticks, then, the women would pray and ask for personal graces. At the end, they would pull the piece of paper: if it ripped and came off the stick, then God would grant their prayers. Magic is meant to be shared.

Truth, on the other hand, is always and only a private and personal matter. Talking about belief and truth, Olimpia and I agreed with Luigi Pirandello’s conclusion that real truth exists only in the mind of the beholder. Sharing it with someone, inevitably generates a new, even if ever so slightly different, interpretation, so that a shared truth, identically understood by two different people is a tautological impossibility. When it comes to physical experience, though, we believe in the things others too can see, hear, smell and touch. To be alone in these perceptions would be madness. The desire to share magic, then, makes sense. An exclusively personal magical system seems like a fool’s business.

Art is a kind of magic, a hermetic system of belief, that exists only because a collectivity keeps it alive. Artifacts loaded with value, yield power thanks to the blessings of a sufficient number of licensed high priests. But there’s something more to it. The magic of some art is that of disregarding any expectation of coherence with social convention, and dare to make meaning out of such disregard.

That is what Daniel Spoerri’s work seems like to me. For his art and his garden, he took the humblest objects of all, and, with the instinct-given authority of a magician, cast a spell on them. The objects became idols and talismans, deriving their power from their material stories and uses, and the self-assigned power of their maker. This magic, I think, is the constant throughout his otherwise diverse practice. Unsatisfied with the credence and symbols of the culture he was within, he made his own, about things, stories and people that were meaningful, true, to him. I see in his snare pictures an attempt to capture time, to freeze a moment, and a cult for objects that are not symbolic but actual tools of conviviality. And their being used is what made them special. I think they were also about his friends and saving instants and small things from oblivion. Unconcerned with the very personal nature of his truth, his instinct was to continue to make and share.

When he turned to making food and hosting meals for people, as a form art, he said something to the effect that this practice was concerned with life itself. The most powerful instincts are self-preservation (food) and reproduction (sex), he said. He chose to deal with food because so many were already dealing with sex, he said. It occurs to me that cicadas don’t need much in terms of nutrients, living simply on tree sap. They can really focus on sex, then, what they sing for.

To set culture and nature apart is a fallacy, Spoerri knew it, and the cicada’s song is more eloquent on this than any literary reference to it. In a beautiful lecture titled Two billion years of animal sound (1999), biological anthropologist Peter Warshall tells the history of animal sound on earth (and on land, outside water). He explains it is a story of the ways creatures evolved to “move air precisely, tune themselves into the air stream, and figure out ways to make a song inside the noise”. Sound-making evolved as a means of communication and therefore needed to satisfy a creature’s need to (1) be heard within the existing surrounding soundscape, (2) be discernible from other similar sounds, (3) communicate different things through a sufficient number of variables. In order to do this, “all creatures on the planet”, Warshall says, “human or nonhuman, possess a sort of creative power to play with the sound stream, a power which is not clearly within one’s conscious will power, but appears to follow its own implicit rules”. This creativity, then, is an instinct. An instinct to articulate desire, which can be sexual, for food, for comfort, for help… To transpose on a symbolic plane an experience of and relation to the world.

A culture is similarly the product of a kind of natural selection of human creations. It is like a song. Just as animal sound evolves continuously to emerge from the growing complexity of its soundscape, so the products of what we would call cultural creativity evolve to fit into or stand out from their ‘culturescape’. Then the process of cultural selection will determine whether they are to be preserved from time, to be saved from inevitable transformation and decay, or not. And so, institutions attempt to protect a version of the truth, a version of the song, from splintering into too many interpretations. That is a culture. Something that keeps us latched onto the idea of a shared reality and keeps us from descending into the chaos that constantly living aware of the fabricated nature of meaning would be. It is a song to follow, to listen to, maybe dance over.

But “without the pressure of the air we get pauses, silence and quiet”, says Warshall. And in those pauses, in that silence, we may catch a glimpse of that chaos. We might despair, consider whether to fabricate our own meaning, or to sing along. Composer and musician Pauline Oliveros wrote “most students do not realize that they have creative potential to make their own music as well as learning to perform”. Her deep listening practice is based on the premise that listening is an active engagement, unlike hearing, which may happen passively, or rather, to use her words, “turning off attention to the auditory cortex”. If we are to partake into the shaping of the sound stream, we must listen.

This is what pause means to me. Creative and transformative power, magic even maybe, lie in our ability to take silence seriously, to make room for it and pay attention.

So I have returned to my boring hours with more conviction than before, determined to listen.

A different story on cicadas

Last, it seems it is left up to me to set the record straight, on life and cicadas.

There was once upon a time a young cicada nymph living underground peacefully. She talked for years about the meaning of life with other cicadas of the same brood. It didn’t make sense to her, to live a life whose primary aim was to produce more cicadas that could in turn make even more cicadas. This seemed the pointless faith of all living creatures, however you looked at it. All had come up with elaborate systems of beliefs that could domesticate the wild sense of void. Ants, ringworms, centipedes, moles… all had different philosophies and organizational structures, institutions and morals the inevitability and goodness of which they never doubted. Obviously, they couldn’t all possibly be right, but no theoretical system seemed more convincing than any of the others either. If the cicada couldn’t logically conclude that they were all wrong, nevertheless she could conclude that all those beliefs were certainly made up.

After years of discussions and thinking, the cicada and her brood couldn’t help but hopelessly think of life as meaningless. However, before dying, they decided they would at least travel up to the surface and see the other side of the world, above ground. On St. John’s night, they climbed up and onto trees. From those heights, in the air, they grew wings to move more freely and meet other cicadas from other parts of the forest. In the morning, the beauty all around, the heat of the sun, the breeze of the wind struck them. Suddenly they felt a burning desire to live, even in a meaningless world. The cicada flew across the pines and the oak trees, in ecstasy. She could hear other cicadas singing about all that beauty. When she finally heard a song that spoke to her, she found the singer and they indulged in hours of love. But, after they reached the peak of pleasure, exhausted, everything looked pointless again. Her partner died there and then. She couldn’t. She realized this was how more cicadas were coming to be into the world, and the work was hers to do. With the little strength she had left, she dug a crack into the tree and laid 500 eggs there. Finally, she too could die. Her last thought was that maybe the next generation of cicadas might be able to bring underground memories from that side of world. Though she immediately realized, that she too, in her time, had been born overground.

[1] It takes its name, apparently, from the fact that even when botanists tried to collect them in herbaria, squeezing the plant between pages, it did not die, and they had to boil it to effectively kill it.

[2] In the English translation of Aesop’s tale, where the proverbiality of the couple originates from, often the cicada (τέττιξ) is translated as a grasshopper.

[3] Though he himself had a brief experience as a slave, after being captured by pirates.

[4] Cicadas’s feed on tree sap only and therefore don’t need to move to forage.

[5] Plato’s tale (258e-275c) is also part of a segment in which Socrates asks Phaedrus to discuss the difference between writing well and badly — so that the cicadas above their heads may report back to the Muses on their philosophico-aestethic endeavors. Phaedrus responds enthusiastically and goes on to say this would be a real delight, unlike eating (or any other bodily gratification), because the pleasure of such a discussion is truly free and does not derive from the satisfaction of some biological need. Phaedrus defines the satisfaction of biological needs as the pleasures “of slaves”, thereby implying a correspondence between freedom, intellectual labor and a higher social status, and conversely a lower social status.

-Benedetta Castrioto

“My curatorial practice builds on the idea that how we do things matters just as much as what we do, and substantively influences the outcome of our work. I believe that the essence of curating is to build bridges, to connect ideas and people. To do that meaningfully, one has to interrogate the political and social dynamics of cultural production and fruition themselves.

I am passionate about multidisciplinary projects. In particular, I am interested in labor, social and environmental justice. Central themes in my work so far have been Land and Environmental Art (with a focus on practices in the Global South), Lefebvre’s theory of the production of space, institutional critique, the politics and philosophy of labor, and material culture.”

Originally from Italy, Benedetta has been living and working in different parts of the world since 2011. She began her journey in the field of cultural production as the Program Manager of Zoma Museum, in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. She has since led and consulted on projects in Italy, the US, Ethiopia, and the UK. Currently, I am based in Accra, Ghana.

She has an MA in Arts and Cultural Enterprise from Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London, and an MSc in Environment and Development from the London School of Economics.

https://benedettacastrioto.com